- BLOG

- CRYPTO-BASICS

- Prediction Markets Explained: History, Polymarket, Futarchy, and Tax Implications (2025 Guide)

Prediction Markets Explained: History, Polymarket, Futarchy, and Tax Implications (2025 Guide)

Prediction Markets Explained: History, Polymarket, Futarchy, and Tax Implications (2025 Guide)

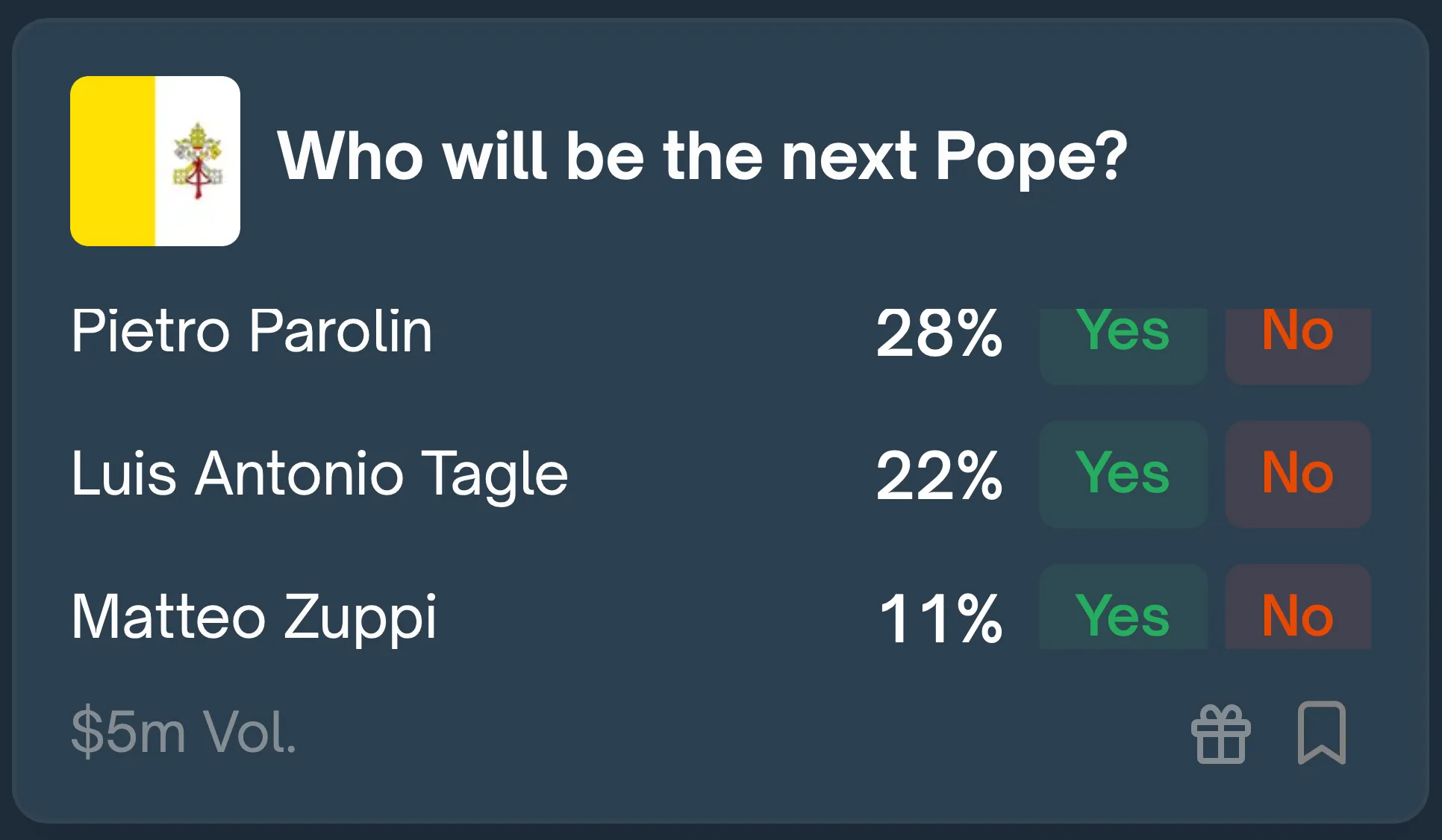

TL;DR: Prediction markets use real-money trading to forecast events, from elections to papal succession. Originating with bets on papal conclaves in the 1500s, these markets now thrive on blockchain platforms like Polymarket, which recently outperformed polls in predicting the 2024 US election. Polymarket is not officially available to users in the US or UK, but some still access it via VPN (against platform rules). Unlike traditional UK betting, profits from crypto prediction markets like Polymarket are subject to Capital Gains Tax or even Income Tax for frequent traders.

The Historical Evolution of Prediction Markets

Origins and Early Development

Prediction markets have a surprisingly ancient history that predates modern financial institutions and scientific polling methods by centuries. The earliest documented political betting event dates back to 1503, when people placed wagers on papal succession candidates, a practice that was already considered “an old practice” even at that time. This reveals that humans have long recognised the forecasting power of wagering markets. Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, betting on governance outcomes flourished, particularly in Italian city-states where citizens routinely wagered on the selection of government officials and papal elections. This tradition of political betting continued to evolve and spread geographically during the 18th to early 20th centuries, with numerous instances of wagers on parliamentary elections in Britain, local and national elections in Canada, and presidential and congressional contests in the United States.

The concept reached particular prominence in the early twentieth century, when major newspapers like The New York Times regularly published gambling odds on elections as a form of public forecasting. These odds were not merely entertainment but served as serious predictive instruments that synthesised public sentiment and insider knowledge into probability estimates. This golden age of prediction markets in public discourse was eventually curtailed by the rise of scientific polling methods, which offered a seemingly more rigorous and systematic approach to forecasting political outcomes. The shift marked a turning point where statistical sampling temporarily displaced market mechanisms as the preferred forecasting methodology for serious analysis.

Modern Revival

The resurgence of prediction markets as respected forecasting tools began in the latter half of the twentieth century, propelled by two significant intellectual developments: the efficient markets hypothesis in finance and innovations in experimental economics. Researchers began to recognise that markets have inherent information-aggregation properties that could be harnessed for predictive purposes beyond financial asset pricing. The advancement of telecommunications technology further accelerated this revival by allowing real-time price information to be shared globally, creating more liquid and responsive markets that could quickly incorporate new information.

Despite this renewed interest, prediction markets still faced significant legal and regulatory barriers in many jurisdictions, with the 1961 Federal Wire Act in the United States, for example, outlawing the use of wired communication for betting or wagering. These restrictions limited the mainstream adoption of prediction markets but also spurred innovation in their design and implementation to navigate legal constraints.

Futarchy and the Significance of Prediction Markets

Understanding Futarchy as a Governance Model

Futarchy represents an innovative governance model conceptualised by economist Robin Hanson that uses prediction markets as the primary mechanism for decision-making. In this system, elected officials would define measures of national welfare, but prediction markets would determine which policies would best achieve these objectives. This approach aims to harness the information-aggregation power of markets to make more effective policy decisions. Futarchy operates on the principle that stakeholders with financial incentives to correctly predict outcomes will conduct thorough research and analysis, leading to more informed and accurate forecasts than traditional decision-making processes dominated by politics or bureaucracy.

The model creates a direct link between prediction accuracy and policy implementation, potentially reducing the influence of special interests and cognitive biases that often plague traditional governance systems. By separating the definition of welfare goals (which remains in the democratic sphere) from the determination of policies to achieve those goals (delegated to prediction markets), futarchy attempts to combine the legitimacy of democratic processes with the efficiency of market mechanisms. This separation allows for value judgments to be made democratically while empirical judgments about what works are determined by market processes, theoretically leading to better outcomes for citizens. In futarchy systems, market participants effectively “vote” with their money on the expected outcomes of different policies, creating an incentive structure where being right is financially rewarded.

Vitalik Buterin’s Perspective on Prediction Markets

Vitalik Buterin, co-founder of Ethereum, has been a long-standing advocate for prediction markets, dating back to his writing about futarchy in 2014. His interest is not merely academic—Buterin was an active supporter of Augur, an early blockchain-based prediction market platform, and has personally participated in prediction markets, earning $58,000 betting on the 2020 US election. In recent years, he has closely followed and supported Polymarket, demonstrating his continued belief in the value of these systems.

According to Vitalik, futarchy could have significant implications specifically for cryptocurrency markets by providing a governance model that aligns market incentives with decision-making processes. This alignment could potentially enhance both market efficiency and investor confidence in the crypto space. In his own writings, Buterin has argued that prediction markets are not merely gambling platforms but powerful tools for information aggregation that can serve crucial functions in society. He views prediction markets as having steady, incremental value rather than creating spectacular overnight innovations, stating that he expects them to “not make extreme multibillion-dollar splashes, but continue to steadily grow and become more useful over time”. This perspective reflects a nuanced understanding of how these technologies gradually integrate into and transform existing systems.

Comparing Crypto-Based and Traditional Prediction Markets

Traditional Prediction Market Platforms

Traditional prediction markets operate on centralised platforms and utilise conventional financial infrastructure. The Iowa Political Stock Market, launched in 1988, stands as one of the oldest modern examples, operating as a non-profit platform specifically designed for educational and research purposes. These traditional markets typically function under specific regulatory exemptions, limiting their scale and accessibility. They often operate with play money or within strict participation caps to avoid running afoul of gambling regulations. Despite these limitations, they have demonstrated remarkable forecasting accuracy across various domains and have been valuable tools for researchers studying information aggregation and crowd wisdom phenomena.

The mechanisms of traditional prediction markets typically involve participants buying and selling contracts that pay out based on specified event outcomes. These contracts are priced between zero and one (or $0 and $1), with the price reflecting the market-estimated probability of the event occurring. For example, a contract priced at $0.75 suggests the market estimates a 75% probability of that outcome. Traditional markets benefit from established financial infrastructure but suffer from regulatory constraints, limited liquidity, and accessibility issues.

Blockchain-Powered Prediction Markets

The emergence of blockchain technology has enabled a new generation of prediction markets that address many limitations of traditional platforms. These crypto-based prediction markets leverage blockchain’s inherent properties of transparency, censorship resistance, and programmability to create more accessible and trustless forecasting platforms. The design of these platforms typically involves smart contracts that automatically execute payouts based on verified outcomes, removing the need to trust a central authority to honour the results.

However, these crypto-based markets also face significant challenges. The technical complexity of current crypto wallets creates barriers to entry for non-technical users, limiting participation breadth. Transaction costs on popular blockchains like Ethereum can be prohibitively high during periods of network congestion, making small-value predictions economically unviable. Market resolution mechanisms remain a thorny issue—determining the “truth” of an outcome in a decentralised manner is non-trivial and can be vulnerable to manipulation. Crypto-based prediction markets have occasionally failed to accurately forecast outcomes, as evidenced by their poor performance during Brexit and the 2016 US presidential elections.

Polymarket: A Case Study in Modern Prediction Markets

Overview and Operational Mechanics

Polymarket has emerged as the world’s largest prediction market platform, allowing global users to trade on highly-debated topics spanning diverse domains including cryptocurrency, politics, sports, and current events. Unlike traditional polls that simply gather opinions, Polymarket requires participants to back their predictions with real money, creating a system where those with greater confidence or better information have stronger incentives to participate proportionally to their conviction. This “skin in the game” aspect is fundamental to Polymarket’s effectiveness, as it ensures that participants have financial motivation to carefully research and thoughtfully evaluate probabilities rather than casually expressing opinions without consequences.

The operational mechanics of Polymarket involve a straightforward yet powerful system where users can buy and sell shares representing future event outcomes. These shares are always priced between $0 and $1 USDC (a stablecoin pegged to the US dollar), with the current price reflecting the market’s collective estimate of the probability of that outcome occurring. Every pair of event outcomes (e.g., “YES” and “NO” shares) is fully collateralised by $1 USDC, ensuring that the platform maintains full reserves for payouts regardless of the eventual outcome. When an event resolves, holders of shares in the correct outcome receive $1 per share, while holders of incorrect outcome shares receive nothing.

Technical Infrastructure and Financial Model

Polymarket operates on the Polygon blockchain, a layer-2 scaling solution for Ethereum that provides lower transaction costs and faster confirmation times than the Ethereum mainnet. This technical choice makes the platform more accessible to casual users by reducing the financial barriers to participation created by high gas fees on Ethereum. Users interact with Polymarket through crypto wallets, which must be connected to the Polygon network to transact on the platform.

The financial model of Polymarket is built around market liquidity and trading fees. The platform collects a small fee on trades, generating revenue while maintaining sufficient liquidity for users to enter and exit positions easily. The collateral system ensures that all payouts are fully funded, eliminating counterparty risk for users. Unlike traditional betting platforms that take the opposite side of user bets, Polymarket acts primarily as a marketplace connecting buyers and sellers of outcome shares, similar to a stock exchange. This model aligns the platform’s incentives with market health and liquidity rather than with specific outcomes, as the platform generates fees regardless of which outcomes actually occur.

2024 US Presidential Election Predictions

Polymarket achieved particular prominence during the 2024 US presidential election, where it consistently showed different probabilities than many mainstream polls and prediction models. While many traditional sources suggested an extremely close race with roughly 50/50 odds, Polymarket consistently showed Donald Trump with an advantage, placing his chances of victory around 60% compared to Kamala Harris at 40%. This divergence from conventional wisdom proved prescient when the election results came in. More strikingly, as results began to be reported on election night, while many news sources continued suggesting the possibility of a Harris comeback, Polymarket quickly reflected the emerging reality, showing Trump with greater than 95% chance of victory and over 90% chance of Republicans seizing control of all branches of government.

Usage Restrictions And Tax Implications

Despite its global user base, Polymarket maintains strict geographic restrictions. Following a 2022 settlement with the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the platform officially blocks access to users with U.S. IP addresses. Similar restrictions apply to UK residents under updated February 2025 regulations, with the platform actively blocking British IPs. These measures aim to comply with derivatives trading regulations, though users in restricted jurisdictions can theoretically access the platform via VPNs - a practice Polymarket explicitly prohibits but cannot fully prevent.

Traditional Gambling vs. Crypto Prediction Markets

The tax treatment of winnings from prediction markets like Polymarket varies significantly between jurisdictions and involves multiple complex factors, especially given the platform’s cryptocurrency-based nature.

In the United Kingdom, the traditional approach to gambling winnings is straightforward: they are tax-free. As clearly stated in multiple sources, UK gamblers do not have to pay taxes on their winnings, regardless of where they play, how much they bet, or how large their winnings. This tax-free status was established in 2001 when Gordon Brown, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, abolished the betting duty that previously applied to gambling activities.

However, the tax treatment becomes more nuanced when cryptocurrency is involved. Since Polymarket utilises USDC stable coin for transactions, this creates potential tax implications as any subsequent conversion of crypto winnings into fiat currency could trigger CGT obligations.

For example, if a UK user were to hypothetically access Polymarket (ignoring the restriction), win USDC tokens through betting, and then convert those tokens to British pounds, the conversion might be subject to CGT based on the difference between acquisition cost and disposal value.

The Comprehensive Guide to Smart Contracts: From Concept to Future Applications

Account Abstraction Explained: How Smart Accounts Simplify Crypto